After five years of waiting, Wayne 'Fella' Morrison's family are still calling for justice

The coronial inquest into Wayne 'Fella' Morrison's death in custody concluded last week, but his family feel they are still no closer to finding out the truth.

Gudamulli!

I want to start by apologising for the sporadic nature of this newsletter. Over the past few months, I’ve been working on finishing my first non-fiction book ‘Black Witness’, to be released by UQP, and also plugging away at my PhD research into media representations of violence against Aboriginal women. It’s been busy, but I’ve also been trying to come back to ‘Presence’, to make this a regular, weekly publication. One reason is that there are so many stories I want to follow up, and the other is that I want to build this publication into a form of independent black media that can in the future cover inquests and court cases through a methodology of ‘Presencing’. Again, I hope you can stick with me! I’ll hopefully bring more updates about the future of the newsletter and its direction over the next month.

Today I bring you a short update on the long-running campaign for justice for Wayne ‘Fella’ Morrison, a 29-year-old Wiradjuri, Kookatha and Wirangu man, who died in custody in September 2016 after being restrained and spit-hooded by prison guards. Five years on, Mr Morrison’s family feel they are no closer to finding out the truth of his last hours, because of the refusal by prison guards to testify on three lost minutes in the back of a prison van when there was no CCTV footage. The inquest finally concluded last week but Mr Morrison’s family have called for a fresh inquiry.

The other story that I’ve been following has been the COVID crisis in New South Wales. Last week, New Matilda broke a story about how the NSW government aggressively knocked back concerns from Wilcannia - first refusing the community requests to go into lockdown back in 2020, and then refusing their requests to adequately deal with the long-neglected over-crowding issue. When COVID hit Wilcannia in mid-August this year, community members were forced to isolate themselves in tents in their own backyards because their long repeated requests to deal with overcrowding had been ignored. Wilcannia Working Party chair Monica Kerwin said:

“They wouldn’t lock Wilcannia down last year to keep the virus out, but once it was here they lock us down in overcrowded housing…The extra police and Army were only sent here for compliance. They weren’t sent here to support anything – they were sent here literally to enforce the law.”

The situation in Wilcannia also made the front page of The Washington Post last week. I’ve heard from many people the crisis in Wilcannia and the way the NSW government has dealt with community members is a common story in other communities, and there are many other smaller Aboriginal communities who haven’t received the attention they need. Again, black communities are forced to protect themselves while being told they are the problem and are struggling to get the airtime they deserve. Even as they fight to protect their communities, they are being blamed for failures that are not their own.

Five long years and still no justice for Wayne ‘Fella’ Morrison

Wayne Morrison (right) and his sibling Latoya Rule.

IN PRISON, there are very few places free of surveillance. You are being watched when you enter, and even when you leave. But despite this intense surveillance, there are ‘dark spots’, and in these dark spots, there is an unknowing, that which is deliberately concealed and left unsaid because to say it would be to incriminate those who this surveillance is actually supposed to protect. For Wayne Fella Morrison’s family, there is a ‘dark spot’ from which they can find no light: less than three minutes in a prison van; the place where Wayne gradually lost consciousness and took his final unassisted breaths.

On September 23, 2016, Wayne Fella Morrison suffered significant injuries after being taken out of a holding cell in Yatala prison in Adelaide. He was on remand and was due to appear at his first bail hearing via video link. But he would never turn up. This was the first dark spot. As his mother Caroline Andersen, sister Ella Russo and sibling Latoya Rule, waited in the courtroom, Wayne was being restrained, placed in ankle fist-cuffs, covered in a spit hood and placed face down in the rear of a prison van. They were told nothing for the next five hours: nothing as he was taken to hospital, nothing as he was put on life support; nothing as they frantically called the department of corrections, and then the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement and then hospital, after hospital, after hospital.

The events leading up to these injuries were recorded on CCTV: footage released during his coronial inquest shows up to 18 guards involved in his restraint; so many prison guards that you can barely see his body. But what happened afterward, in the back of the prison van, is unknown. This was the other dark spot. There was a CCTV camera in the van, but evidence provided shows a prison guard’s head was blocking the camera. What happened in the back of that van is known only to the eight prison guards who were there with Wayne. What we do know is that in that when Wayne was removed from that van, approximately three minutes later, he was unconscious. There was a delay by prison guards to administer CPR, and Wayne wasn’t breathing for up to 50 minutes. By then, his injuries were so severe he would never recover. He was taken to the Royal Adelaide Hospital where he died three days later, in the presence of his loved ones, and the prison guards charged with surveilling him even as he took his last breath.

Last week, a coronial inquest into Wayne’s death concluded. It had taken five years to get to this point, but even during the inquest, the proceedings were delayed by 18 prison guards and a nurse who went to the Supreme Court to argue that they should be able to claim ‘penalty privilege’ in case of self-incrimination. They also tried to get the deputy State Coroner Jayne Basheer removed from the inquest claiming apprehended bias. While the request to remove the Coroner was refused, the Supreme Court upheld the right for the prison guards to claim ‘penalty privilege’, each individually when being called to give evidence. For 3 years, Wayne’s family was put through the stress of a delayed process because the guards felt they should not have to give evidence, and when they were back on the witness stand, each of them continued to claim this ‘penalty privilege’.

A range of Aboriginal women - legal academics and educators - attended the inquest to report on daily updates, they wrote of their frustration in the process, by chronicling how each prison guard refused to answer questions by claiming ‘penalty privilege’. At one point in the inquest, they recount how the Coroner herself expressed her frustration.

I will not tolerate any further delay in these proceedings and have the Morrison family sit at the back of this court and be subjected to what they must wonder is a derailing of their one hope that this inquest might actually probe something that was of interest to them.

All they have seen from start to finish is a display of lawyers asserting what I accept is their legal rights. But if you think I am frustrated, it is because I am.”

Now, five years after Wayne died, approximately 3 years after the inquest began, the closing submissions have been made, but Wayne’s family are no closer to finding out what happened in that ‘dark spot’. They have called on a further inquiry into his death.

For a place in which ‘surveillance’ is so important, it is very telling to me that there is a continual attempt to conceal these ‘dark spots’. Wayne’s family has already been placed in these positions so many times, from the very first day that Wayne was arrested, when they made numerous calls to enquire about his welfare while in custody, with concerns about his health and wellbeing. They were knocked back or given no information or told to ring back. They were given no information on the day of Wayne’s bail hearing, about the events that would lead to his death; until far late in the afternoon when they lost hours by his bedside because they had no idea where he was or if he was safe. And in this process, they have been continually placed in these dark spots of not knowing through the delays and the legal wrangling; so frustrating that even the Coroner expressed as such. All these legal arguments go around and around to address the central, glaring point: why did my son die, and who was, and should, be held responsible?

Of course, the most glaring dark spot, the one that encompasses everything are those spaces in which they lose Wayne again: the justice system that sees Aboriginal men as criminal; or does not see them at all (despite his name being a well known Aboriginal family name, the prison staff claimed they first did not recognise him as Aboriginal); or in the media where he is just another, brutalised black body. He is none of those things: Wayne as known by his family was a larrikin, a lover of life, an artist, a weaver, a fisher, a man who had a big life ahead of him. He held his Aboriginality close; it was the essence of who he was.

In the face of these ‘dark spots’, in the face of this unknowing, the family have continued to fight for justice for Wayne through abolitionist methods and last week won a historic state-wide ban on spit hoods. The law, soon to pass the lower house, is called ‘Fella’s Bill’. While Wayne’s family say they understand that banning this device, which contributed to Wayne’s death, may not provide justice for Wayne - they are glad their advocacy means that no other individual or family will experience this ever again. From here, the family calls for a Royal Commission into Wayne’s death and a national ban on spit hoods.

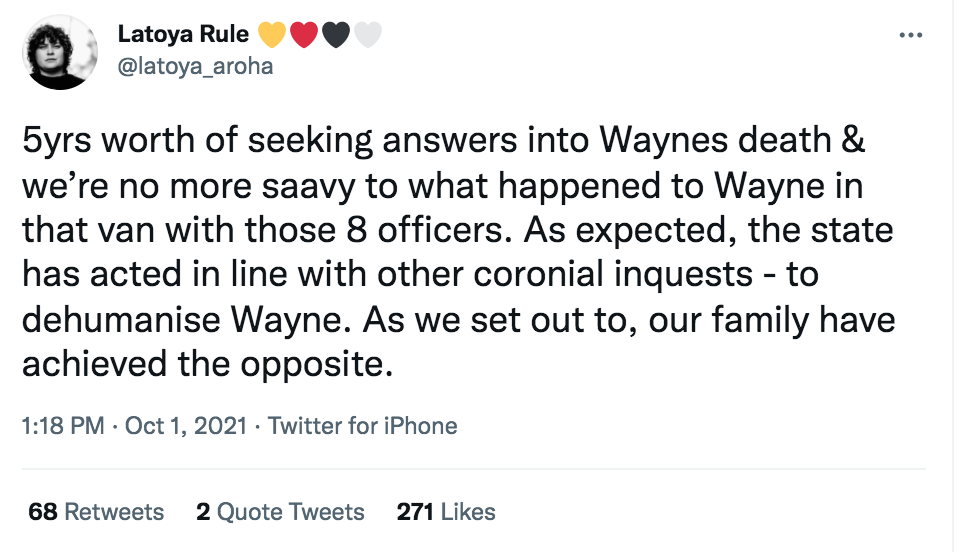

I have known Latoya, Wayne’s sibling, over the past five years, and have witnessed the strength and tenacity of their family in pushing for a ‘justice’ that is not recognised by legal processes. In a tweet last week, Latoya wrote:

Coronial inquests are supposed to be truth-telling exercises, but so often, for Aboriginal families, the process works to conceal the truth; to further entrench these ‘dark spots’, to further dehumanise Aboriginal people who have died at the hands of a violent ‘justice’ system while legitimating these processes; making them a matter of ‘procedure’ and ‘protocol’ rather than what we know it to be: racial violence. By standing up and actively resisting this, by making visible this violence through Aboriginal women who came to witness the inquest proceedings, by supporting other black families in their fight, and by spearheading an abolitionist campaign that will undeniably help other black families, Wayne ‘Fella’ Morrison’s family has shown us how powerful they are.

I’m aiming to make ‘Presence’ a weekly newsletter, filled with analysis of the justice system and short updates on cases and issues I am following. If you would like to stay updated, please subscribe.