Black Witness: Reading Ida B Wells in this place

There is a strong tradition of black journalism both in this place and overseas. They have given us a foundation to build upon.

Gudamulli,

Thank you so much to everyone who subscribed last week - it meant so much to see the article on Silencing shared across social media and I hope it also gives you an insight into where I’m going over the next month. I’m currently researching a few stories that I hope to publish by November. They are cases I’ve been wanting to follow up for a very long time. One of those stories is on the repatriation of Wakka Wakka woman Queenie Hart, who will return to country later this month. The readers of this Substack, and the Guardian, as well as Pay The Rent down in Melbourne helped fundraise for her to return home to country. I just wanted to say thank you for your ongoing support.

One of the reasons I launched this Substack is because although I have been fortunate to have opportunities as a freelancer in mainstream media, I feel like I can write differently here. When I write for mainstream media, I always have this niggling voice in the back of my head - I must make this palatable, I must tone this down - and even though I try to suppress this voice, I find it something of a battle. When I write this Substack, in my own methodology and using my own Indigenous storytelling methods, I find that there is a certain freedom. I have never really written for the white gaze, as Toni Morrison has termed it because I’ve been fortunate to mostly work in black media, but the white gaze can still feel ever-present.

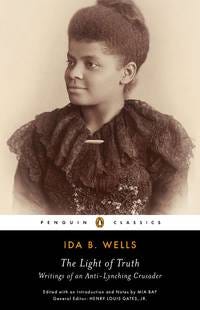

With that in mind, and as I continue to focus on a few stories that require a bit more time, I’ve decided to go in a different direction for this week’s update. Earlier this year, I was gifted a collection of Ida B Wells’ journalism by my PhD supervisor and mentor, Dr David Singh, who is a co-director at the Institute for Collaborative Race Research and a leading critical race scholar in this country. I was at the office one day and saw it on his desk, and I asked him about it. He began telling me about Ida and her work, and then he paused and said I could have the book because I was working in the same tradition. I thought that might have been overly generous as Ida B Wells is legendary, but Dr Singh’s gift was not only in acknowledging the similarities in black journalism over there, and in this place, but in the gift of learning and sharing, in building upon the legacy of those who have gone before us. I’ve been reading it slowly, going back to it, letting her journalism wash over me. I thought I would write a short dispatch of what lessons we can take from her amazing journalism and advocacy over here.

Just this morning, I realised how important this was when I read former The Age editor Michael Gawenda’s long piece in the same paper today. The piece interrogating The Age’s coverage of Indigenous affairs over the last century. He says the paper’s first dedicated Indigenous affairs reporter was appointed in 1993, and was white, and from then on, until very recently, that has been the case: “the journalists who dedicated themselves to reporting on Indigenous issues – either because they were asked to do so by editors or, more often, because they decided that this would be their main work – have been mainly middle-aged men,” he writes. The piece follows on from another long form article by Biripi journalist, and new Indigenous affairs correspondent at The Age Jack Latimore, who wrote of the history of black media. I really liked Latimore’s piece but had some issues with Gawenda’s, which I will explain more about below.

In reading Ida B Wells, I’ve often been thinking about how we should keep questioning basic journalistic principles which do not work for blackfellas or the goals of black media in the pursuit of black justice. One of these principles I’ve been thinking of lately is the ethics of ‘breaking’ a story; being the ‘first’ and claiming ownership over stories. This is something I will hopefully be thinking and writing more about over time.

If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing and sharing!

Reading Ida B Wells: The Black Witness

I have always known that to be a black journalist, is to be an advocacy journalist, in the words of the legendary African American reporter Ethel Payne. That is because, the tradition of black journalism in our own country, has always been one of advocacy, from the very beginning, but sometimes I feel that the current focus - to have a voice, and space, in the mainstream media means we compromise this position. The conversation is often focused on ‘diversity’ in the media, rather than building a sovereign black media space totally independent of government. I believe that our black media must be an arm of advocacy, not simply one who reports on this advocacy, but a weapon to be used by mob in the pursuit of justice.

That is fundamentally different from the ways White journalists and white media have viewed coverage of Indigenous affairs. White media only sees blackfellas through a binary lens of ‘victim’ or ‘perpetrator’. This was evident in Michael Gawenda’s piece in The Age today, in which he lamented the paper’s focus on ‘Indigenous victimhood’. He claims that this meant the paper could not adequately scrutinise Indigenous communities and leadership, for example, in the case of former ATSIC leader Geoff Clark, where the paper received criticism from readers who claimed they had ‘betrayed’ Aboriginal people through the coverage.

This is a common trope in mainstream media analysis of Indigenous affairs, which is such a limited debate, focusing on whether white journalists have the ‘right’ to tell black stories, whether ‘everyone should speak on black rape’, whether black writers are properly equipped to tell stories of ‘violence’, but only ‘interpersonal violence’, never the violence of the state. Black journalists are seen to be biased; to be unable to see beyond our ‘race’; whereas white journalists don’t charge themselves with the same thing.

Black writers write on violence not to pursue a narrative of ‘black victimhood’ but to refocus the lens on a settler colony that still uses violence to enforce a racialised heirarchy. This is not about ‘black victimhood’, it is about white violence, and yet to tell the truth of this, is to apparently play the victim card.

Reading Ida B Wells, the legendary black journalist and anti-lynching crusader is to read a masterclass in revealing this violence, not by proclaiming this white version of ‘victimhood’, but by positioning black people in positions of strength that have been denied them; by confronting the lies that justify the violence. Ida courageously worked directly in the face of this threat.

By 1892, she was a prolific journalist, writing for the Free Speech, where she travelled up and down the railroad, writing directly for black people. It was at the Free Speech that she wrote fiercely about a triple lynching in Memphis in which three black men died, including her friend Tommie Moss. Wells did not stay silent: she used her pen as a weapon, writing a series of editorials which cut to the heart of the racist lies about black men; that this was not about rape, but a form of racial terrorism. The three men had been running a successful local business, and had been targeted because of the threat they posed to white businesses. Wells and the Free Speech wrote of the truth of this - the basis for the violence. On May 21 1892, she wrote an editorial:

“Eight Negroes lynched since the last issue of Free Speech… one at Little Rock, Ark, last Saturday morning where the citizens broke into the penitentiary and got their man; three near Anniston, Ala., one near New Orleans; and three at Clarksville, Ga., the last three for killing a white man, and five on the same old racket - the new alarm about raping white women. he same programme of hanging, then shooting bullets into the lifeless bodies was carried out to the letter.”

Wells as the Black Witness was directly confronting the normalisation of the brutal violence of lynching, and this was such a threat that a white mob descended on the offices of the Free Speech after this editorial was published, destroying the paper and sending death threats to Wells. Wells was forced to the East Coast, where she continued her anti-lynching fight at other publications. Wells did not back down; did not provide concessions; did not offer any false display of ‘objectivity’. As a Black Witness to the lynchings, to the racist terror, she confronted the lies that viewed black men as rapists while also confronting the lies that black girls were unworthy of justice when they were the ones being victimised by white men.

In 1893, Wells gave a speech to the National Press Association called ‘The Requirements for Southern Journalism’, in which she called on the Southern Press to come together as a collective to fight the one-sided accounts of this violence.

“At present only one side of these atrocities against a defenceless people is given, and with all the smoothing over is a bad enough showing,” she said.

Speaking of the Memphis lynchings, she said:

“The Free Speech gave the facts in the case, exposing the rank injustice and connivance of the authorities with a white grocery keeper whose trade had been absorbed by young colored men: how he set a trap into which they fell, and that although the wounded deputies were pronounced out of danger, these men were lynched in obedience to the unwritten law that an Afro-American should not shoot a white man, no matter what the provocation. Our paper showed the character of these men to be unblemished, gave the sketches and cuts of three as reputable and enterprising young men as the race afforded who were prospering in a legitimate grocery business; published a formal statement from our leading ministers addressed to the public; printed 2000 extra copies and mailed them to the lead dailies, public men and Congressmen of the United States. And so in part was counteracted the libel on these foully murdered men.”

This not shows only the power of the Black Witness, in seeing the violence, but in the power of black journalism in not only reporting the ‘other side’, the side of those who had not been defended but instead vilified in death, but in doing the work to ensure the real truth is known; not only in writing the story, but in disseminating it, in strategising for an outcome. Wells did not accept ‘accepted truths’; the accepted narrative put forth by white authorities. I thought of this in how we still give weight to the evidence of white authorities, over the voices of Black Witnesses. Often in stories, the police or government version of events are seen to be legitimate; and the very valid questioning of blackfellas are seen as irrational or angry or overly emotional. The work needs to be done to support the testimonies of Black Witnesses who know intimately the violence because they are the ones who view the reality of this violence and can provide the most truthful accounts of it.

Wells also spoke of the power in resisting representations in the very same speech: “To read the white papers the Afro-American is a savage that is getting away from the restraint of the inherent fear of the white man which controlled his passions, and from whom white women and children now flee from a wild beast. This impression has gained ground form the white papers, and has blasted race reputation in many quarters.”

Wells criticised the black papers who “has not troubled itself to counteract this opinion”, and said “the clearing of this odium attached to the race name is not only the duty of one section but belongs to all, and the National Press Association should no longer sit idly waiting for the garbled accounts of the Associated Press, which it in turn gives the world.”

Wells was able to articulate how these damaging representations were in itself violent and had a purpose in legitimating the violence of lynching; and how the role of the black press was in resisting this at every point. This is a key part of black journalism in our own country - we must be on hand to resist these ‘garbled accounts” of the mainstream press and not through shoddy work, but through investigative, forensic work told through the lens of the Black Witness, and predicated on the strength of our communities.

In the face of the continuing brutal violence of the colony, in the face of these same representations that have been reproduced from the days of the frontier til now, I don’t think the conversations should be on finding a place at the table in the mainstream press. Wells did not do the work she did for rewards, or for applause from white audiences. She did it because she saw the power of the black press and its role as an arm of advocacy. The mainstream press is not set up with the same aspirations of black media. These aspirations are founded in black justice, and are told not only through the Black Witnesses over there, but also here, in this settler colony. Because of this, we should abide by our own ethics of journalism and question the basis of what is a ‘good journalist’ from a western perspective.