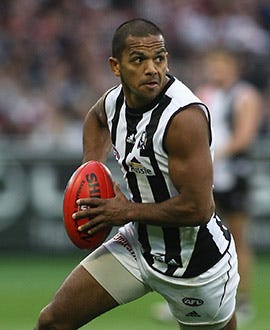

Leon Davis speaks out about racism at Collingwood

The former Collingwood star is still waiting for a call from his former club after spending over a decade enduring racism

Gudamulli!

Whenever a racism scandal erupts in Australia there are several misconceptions made. This emerges from the fact non-Indigenous or white Australians think they have the tools to identify racism, to determine what is racist and what isn’t. There are attempts to find other explanations that ultimately undermine the testimony of the Black Witness. Black Witnesses should be believed because these are never isolated events. We know how to identify racism because it is a reality in this country - it is not just the interpersonal acts of racism, defined sometimes as ‘casual’, but the deeply ingrained structural racism that has a purpose, that was entrenched in order to justify the theft of this land. This racism has never been eradicated.

That structural and systemic racism is what was so powerfully identified and made visible through the damning report co-authored by distinguished Professor Larissa Behrendt and Prof Lindon Coombes in their ‘Do Better’ report into racism at Collingwood (the report was the work of an All-Aboriginal team at UTS).

When Aboriginal, black and POC folk are the victims of racism, particularly in workplaces, there are tactics of resistance and survival that are employed that are not identifiable to white Australians who have never had to deal with it. These tactics are then weaponised against them when they emerge, just as they were weaponised against Heritier Lumumba - who spoke out powerfully against the racism he endured and then was ostracised, mocked and gaslit by the club and media who were spoon-fed and regurgitated the club’s lines (see Aamer Rahman’s powerful Twitter thread about this).

That’s an introduction to today’s piece, which The Guardian published this morning. I spoke to Leon Davis - a proud First Nations man who spent 11 years at Collingwood. The past few weeks has only re-opened past wounds of his time spent as one of the most high profile players at the Pies. What I thought was most powerful was how Davis speaks to his own survival tactics when the first incident of racism was not dealt with properly. It was the aftermath of that incident that was most hurtful. Now he is still waiting on a call from Collingwood.

Leon Davis is still waiting for a call from Collingwood

For the past few weeks, proud Balardong Whadjuk man Leon Davis – who donned the Collingwood black and white for 11 years – has been waiting for a call from the club.

He waited as the details of the “Do Better” report into racism at the club, conducted by distinguished Prof Larissa Behrendt and Prof Lindon Coombes, was handed to the Collingwood board. He waited as the report was leaked on the front page of the Herald Sun, and as outrage grew over its findings that there was systemic racism ingrained in the club.

He waited as Collingwood held a press conference at which the then president, Eddie McGuire, claimed the club was not “racist or mean-spirited” and said: “We’re doing something. We called things out six years ago … in fact 22 years ago, when we started on this campaign.”

He waited as his former teammate and friend Héritier Lumumba – who had spent a decade being racially vilified at the club, then was ostracised for speaking out – continued his strong resistance by calling out the rhetoric and pushing for change.

He is still waiting, even after McGuire’s resignation – not just for a call from the club, but for more information about what comes next. Davis says the issue of racism at Collingwood, and in wider society, is much bigger than one person.

“Everyone is missing the point,” Davis tells Guardian Australia. “Eddie stepped down, but there is a general feeling that it is all done and dusted.”

“I don’t take any pleasure from Eddie stepping down. The issues have not gone away. It still continues, and it will continue for a long time until the true history is known and everyone is better educated about us First Nations people. We wake up every day with the same issues and the same fight and nothing has changed for us. I’m still very disappointed and pretty hurt.”

The events that led to McGuire’s resignation are personal for Davis. Collingwood’s failure to deal with racism, its refusal to acknowledge it, or to heal the past, have forced Davis to confront his own experiences of racism at the club. The proceedings of the last few weeks have resurfaced that trauma. He says it has tainted many of the good memories of playing for a club that he still loves.

For more than 11 years on the field as one of Collingwood’s most high-profile players, Davis says he endured many racist incidents, which were never appropriately dealt with by management or the board. They began within a few months of joining the club, when he was still a teenager.

In 1999 Davis was a new recruit to Collingwood. He had been drafted as an 18-year-old from his home town of Northam in Western Australia, where he had grown up as part of a strong family and community. His parents had instilled in him strength and pride in his identity. He hadn’t wanted to leave them but the opportunity to play at Collingwood – his mum’s favourite team – was the realisation of a long-held dream to play in the AFL. He was excited, though the club’s racist past hung over it.

We were told 'go your hardest' examining racism at Collingwood. Here's what we found

“My closest mates and some family started to question it,” Davis says. “They’d say, ‘Oh, you know they have got a back history of racism,’ or, ‘They’re a racist club. What are you going there for?’

“But I always wanted to play footy, and that was my mindset. And you know I had two paren‘I felt like it was myself up against a big powerhouse of multiple people, an industry, a nation.’ Photograph: Robyn Sharrock/The Guardian

“I was the odd one out of the group. In the room I just felt real little … I went home and my younger brother seen the profile. I wasn’t sure how to react. I was a bit torn about what to do with it and confused. Do I bring it out and rock the boat and get people in trouble, or is it going to stop me from playing footy? Will it jeopardise me staying there and living my dream? All these things were going through my mind.

“I just took it home, went home and told my brother and he said, ‘This is bullshit.’ He got angry and that’s a normal reaction for me and my two brothers whenever we faced that stuff growing up.

“When my parents found out about it, we were packing our bags that night. I didn’t have a say in it. Mum and Dad said like, ‘We’ve put up with this shit all our lives. We’re not putting up with it, that’s for sure.’”

But Davis wanted to play football – it was his lifelong dream. And so, instead, they called a meeting.

“It got sorted out to a certain extent, but it wasn’t dealt with the right way for sure. Back then – it’s similar now – people didn’t have the tools to deal with these issues.”

Davis says there were no repercussions for the players involved but he suffered consequences. He felt ostracised and alone.

“It was the aftermath that probably affected me the most,” he says. “Because then it went to being outcast and not in the in-crowd and finding my way on my own, that kind of stuff which was really difficult. It didn’t last forever, but it was something that was difficult.

“It’s a football club mentality. You’re all on a team and you’re supposed to have everyone’s back. After that [incident] it changed dramatically, where it was hard to be there.

“And then a lot of things happened and I didn’t tell my mum and dad because I felt it would cause the same repercussions for myself. I wasn’t in the group like I used to be … sitting around the table with the boys and being involved … months after that, because I’d been the one who had gone to the club and sort of dobbed on them.

“You can’t put things in place moving forward if you can’t deal with the past.

“It was really hard for me to be there, not only as an 18-year-old kid but being a First Nations man, where there wasn’t any understanding of what I was going through.”

Advertisement

Those early experiences of not feeling understood, of not believing the club had dealt with it properly, influenced Davis’ tactics against racism.

When it happened again, Davis would deal with it one-on-one, or he would try to educate people himself. He says he developed a reputation in the club of not standing for it. Just like his friend Lumumba, who endured 10 years of racist nicknames, Davis employed tactics of survival.

“I’m not coming out to stick it to Collingwood or get people in trouble. I’m coming out to say this happened, this is what continues to happen. And we want better. We want our kids to have it better. We don’t want our kids to have to go through the bullshit we did and our ancestors did.

“I can completely relate to Héritier and what he did to survive because you go into survival mode. And I did. I felt like it was myself up against a big powerhouse of multiple people, an industry, a nation. A lot of times when racist incidents have happened, that’s what it is. We’re up against a nation.”

That’s why Davis is speaking out now. When he heard McGuire at the press conference say this was “22 years ago”, he thought, “Well, that was me. That incident with me happened exactly around that time.”

It’s also why Davis has been waiting for a call from Collingwood, just as he waited for more than a decade while playing at Collingwood for these issues to be rectified. The report is a vindication for him, and all other players who endured racism within its walls, but it is a wider story of the racism in Australia.

“It’s the same with our history and Australian history. What has happened to our people from settlement that hasn’t been dealt with, that hasn’t been rectified. We haven’t had our cultural healing. On a lesser scale with Collingwood, that hasn’t been rectified.

“Until you fix what happened with the past and you make right this environment of systemic racism, this ignorance, this white privilege, I don’t think it’s going to change. With the review, you can’t put things in place moving forward if you can’t deal with the past.”

Now, when Davis goes back to the club, it is what dominates his memories. Its response to the report has only heightened that, leaving him “disappointed, hurt and disheartened”.

“It has been exhausting to deal with the hurt and frustration not only for me but also the way it had impacted on my family, friends and community. I believe that the club’s response stemmed from the systemic racism imposed from the country’s leadership and white privilege.

“When Aboriginal people see missed opportunities to show empathy and ownership it opens up the transgenerational trauma wounds that we endure.”

Until things change at the club, he says he would not want the same life for his children. He has three sons and two daughters.

“One of my sons might want to play footy, but unless there’s drastic change, I wouldn’t subject them to going there without the right things being in place.

“That’s why I want to speak out now: to tell my story, to put things in place for the future for not just my sons, but for everyone that aspires to play football.”