On the ethics of True Crime

Centring victims of violence in the wake of Netflix's Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story

Gudamulli - and I hope you are doing well!

Over the last year I’ve been busy completing my doctoral research into the active disappearing of Aboriginal women in the colony, and how we build up a sovereign black media contest dehumanising and violent representations. I started my research looking at ‘media representations of violence against Aboriginal women’, and then, through the stories of Aboriginal women who have lost their lives to violence, I realised that this framing was limited. This wasn’t solely about violence against Aboriginal women, which is often framed as interpersonal, but instead about the framework of disappearance in which Aboriginal women who have been deemed ‘missing’ or ‘murdered’, are not considered worthy of investigation or justice, even in the limited western sense. I realised that through a framework of disappearance, we see how there are many actors involved outside of the original perpetrators - those who maintain and reproduce the conditions that target Aboriginal women specifically for violence - not just the police, the wider justice system, the media but also the state.

There is currently a Senate Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Children underway, led by two First Nations women - Greens Senators Lydia Thorpe and Dorinda Cox. It is open for submission until November 11.

While I finish the submission process for my PhD, I aim to continue working and writing on the disappearances of Aboriginal women, and hope to continue building this platform in which to do so. Last week Martin Hodgson and I also dedicated an episode of Curtain The Podcast to the issue, if you would like to hear more.

On Sunday, I published something a little different on The Guardian. One of the key questions I’ve wanted to answer over the past few years has been: how do we write stories or represent violence, without reproducing that violence? How do we write on violence without centring that violence? I was reminded of these questions when I saw the debate that emerged over Netflix’s most recent drama on serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer story - which has become the streaming service’s second most successful programme ever, and is still the number one television show on the platform in Australia. The salacious interest in Dahmer at the expense of those who had died, and their families who still grieve for them felt like an extreme example of the continual ethical problems surrounding the genre of ‘true crime’.

Here I wanted to share the full piece, as it was a bit long to be published in full. I hope that as the year continues, I will be more proactive on this platform.

The ethics of True Crime

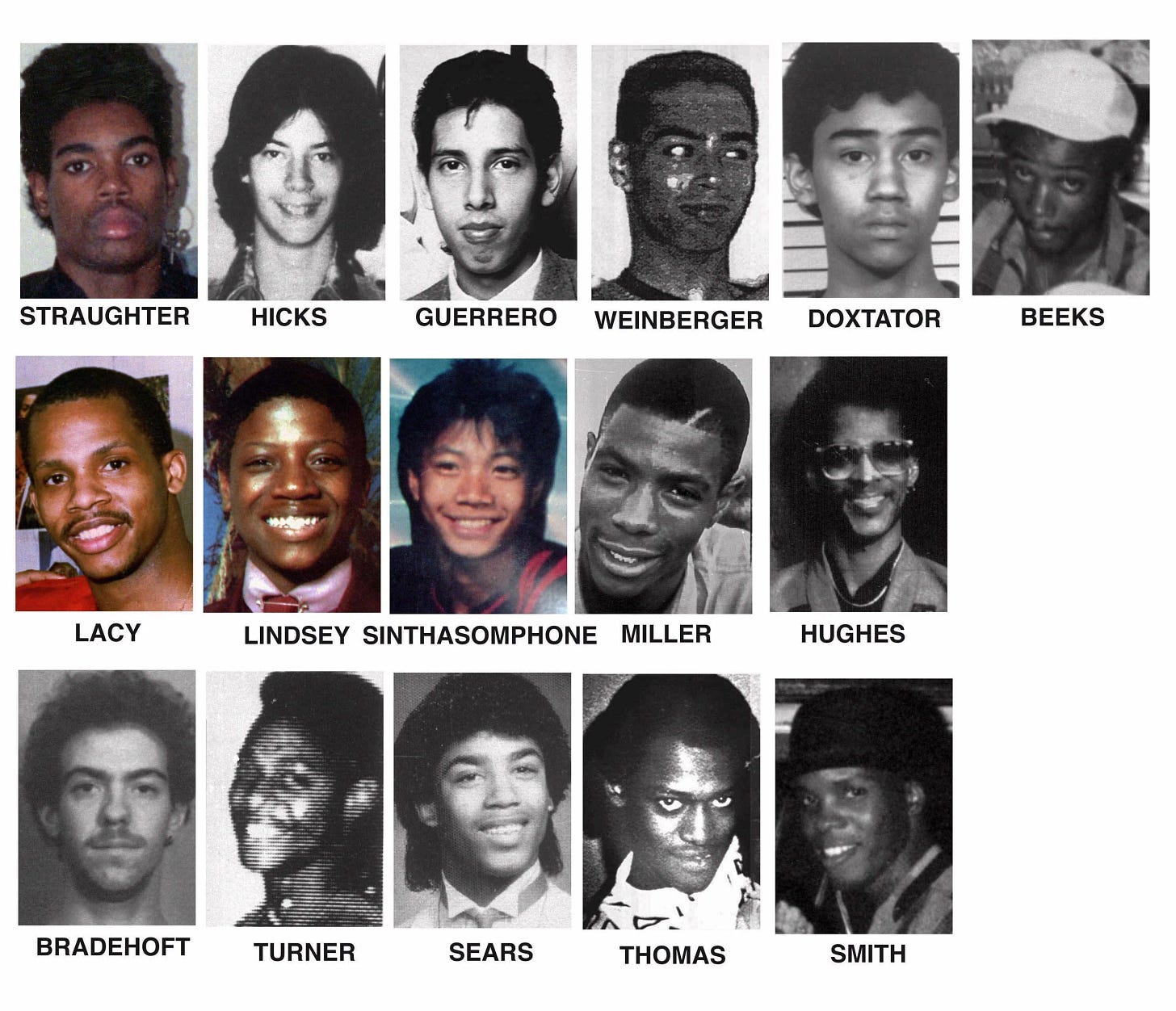

On the last day of the trial of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, the families of the young men and children who had lost their lives at his hands, gave victim impact statements to the court. Some of these statements have been re-created in a controversial new Netflix docuseries Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story which has become the platform’s number one show worldwide. But there was one statement that was not shown.

On that day, Stanley Miller, the uncle of Ernest Miller, appeared with a large photo of his nephew pinned to his suit pocket. With clear, and concise words, Stanley spoke of his family’s distress at the loss of Ernest – who was a natural born dancer and dreamt of taking his talents further.

In his statement, he addressed Dahmer, who sat emotionless: “Despite the fact that you had the knives, the saws, the vat, the acid, the drills and possible a gun, when he was in a semi-conscious state of mind, you didn’t give him a chance to fight for his life. You took his life like a thief in the night…. Rather than facing him and let him fight for the things he felt most dear, you took the coward way out.

“Did you ever stop to think that this is someone’s son? Did you ever stop to think that this was someone’s brother, nephew, uncle, cousin, grandson or just someone’s friend that’s missing him dearly?”

These words, that Ernest was never even given the chance to fight for his life, and for everything that his life embodied, were profound. In the many documentaries, books and relentless commentary on Dahmer, there has been a focus on an idea that Dahmer’s crimes had been perpetrated while the men and children were in an unconscious or semi-conscious state. Dahmer’s interest was not in the act of killing, but in the dehumanising acts that came afterwards.

This is sometimes spoken of as if it was perhaps merciful, and yet it is, through the words of Stanley Miller, a profoundly cruel act. Through his actions, the men and children were depersonalised to the extent that they became less than people, not just at the time of the murders, but afterwards, through the violent re-telling of their stories which is limited to the brutal descriptions of their bodies, and not on their personhood. They have always been denied their right to fight.

In his book The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer, named after the horrifying, alter that Dahmer had designed, Brian Masters described the victims impact statements as a “rough mediaeval spectacle”. He claimed that providing voice to the families was an “American ritual, at once moving and barbaric”. The idea that giving a voice to the victims, through their families, could be ‘barbaric’ in the face of the enormity of what had been done to them speaks volumes of how victims are treated and seen as afterthoughts or affronts to ‘justice’. Rather than repatriating their memory, rather than centring them, the killer is centred. It is his ‘shrine’ that is spoken of, and not that of the families. There is a continuum of violence that doesn’t end but is supported by media portrayals that only leads to further hurt and pain.

The recent Netflix series has led to a conversation on the ethics of true crime, and particularly on what has been seen as the glorification of serial killers, and the intense interest in them and their crimes. Some have claimed the series provides a new insight into the victims, with its focus on the life of Anthony Hughes, while others have stated that it is just more of the same. But what is unchallenged is that, just like so many portrayals of Dahmer, the victims’ families’ have never been given the right to speak to their loved ones.

Rita Isabell, the sister Errol Lindsay, had her victim impact statement recreated in excruciating detail in the Netflix show without her consent, and this was shared widely across social media. Isabell told Insider.com that at the time of her victim impact statement, she wanted to show what it was like to be ‘out of control’ because that was a defense used by Dahmer’s lawyers to argue for insanity.

She described the victim impact statement as moment when she was out of her body, and yet, when the Netflix documentary aired, she had found that control had again been taken away from her over her likeness: “If I didn’t know any better, I would’ve thought it was me. Her hair was like mine, she had on the same clothes. That’s why it felt like reliving it all over again. It brought back all the emotions I was feeling back then. I was never contacted about the show. I feel like Netflix shouldn’t asked if we mind or how we felt about making it. They didn’t ask me anything. They just did it”.

Just like the 15 men and two children, who were denied their right to fight for what they held dear, the families have been continually denied their right to fight for the memories of their loved ones, who had names and those who cared for them: Steven Hicks, Steven Tuomi, Jamie Doxtator, Richard Guerrero, Anthony Sears, Ricky Beeks, Edward Smith, Ernest Miller, David Thomas, Curtis Straughter, Errol Lindsey, Anthony Hughes, Konerak Sinthasomphone, Matt Turner, Jeremiah Weinberger, Oliver Lacy and Joseph Bradehoft. Dahmer took control over their bodies, and the continual salacious interest in Dahmer has taken the control from the victims’ families, to speak to the presence of their loved ones in their lives, and the effect their absence had on them, even now.

Today, when you search for the names of the men and children, you find only brief accounts and grainy pictures. Many of these pictures immortalise them in how they are remembered: as young and free. But readily available on the internet are the pictures that Dahmer took himself, told through his eyes, and re-told again and again, always through his prism: as bodies for his own use, as bodies he could control, as bodies who were not worthy of a future and even more extreme, as body parts, disconnected from their whole personhood.

Many of these young men were black, and many of them were black and gay. The geographies of their life journeys are depicted as always orientated towards a dangerous encounter with a serial killer, and not of how they navigate the violence of a racist and homophobic society; how they must have gravitated towards spaces they considered safe, not just amongst their community but also within their family structures. One of the boys Jamie Doxtator was Indigenous. The Netflix series depicts him as an adult man and gives him no further representation outside of him sitting on Dahmer’s couch with the perception that he is an inevitable and ungrievable death. The other boy, Konerak Sinthasomphone, could have been saved if not for the racist and homophobic actions of the local police who saw no evidence of injury and trusted the word of the white man over that of black women who came to his aid.

The retellings of the Dahmer story are always focused on how a man could become a monster, or whether he was always a monster. There are brief glimpses in the Netflix show of how a racist, homophobic society could provide conditions for him to kill; suggestions that there is an impunity that allows for the killing of predominately young black men. But there is less focus on how a society founded on stolen Indigenous land and stolen black bodies, a society founded upon white supremacy - a settler-colony - could provide conditions for the extreme dehumanisation that was perpetrated by Dahmer himself. His acts were not just because of the need for sexual gratification, but also the delight in extreme forms of terror that are always perpetrated against black and Indigenous bodies. The focus is individualised – what in Dahmer’s childhood made him like this – and not about the conditions that make them the targets for such extreme levels of violence.

These conditions not only make it possible for a serial killer like Dahmer to exist, but also are conditions that make him the mode for which to satisfy an irrepressible appetite for violence fed by the genre of ‘true crime’. It’s these conditions that mean he is occasionally seen as an object of ‘sympathy’, or as an anti-hero, or a caricature to be mimicked in Tik Tok videos with belated explanations that ‘I just like the actor, not Dahmer!’. These conditions mean that the voices of victims are continually silenced.

The conditions we see as normal mean we are all complicit in the ways that true crime becomes entertainment at the expense of the men and children who have died, and all victims of crime. Meanwhile, the victims’ families must deal with the re-surfacing of grief and trauma because the lives of their loved ones are always told through the eyes of the killer, and never by their own testimonies. They are again part of the ‘shrine’ of Jeffrey Dahmer, when they should be repatriated back, their stories only told through the love and care of those who always loved and cared for them, outside of the cycles of new ‘true crime’ shows and podcasts. It doesn’t matter if a true crime portrayal is done ‘sensitively’ if it still takes control away from the victims and their families.

In 1992, Stanley Miller, again spoke of this in an interview with the Los Angeles Times: “Every time you think you’ve got it under control, something else happens”, he said. The newspaper reported the unwelcome reminders “come in many forms: books, serial-killer trading cards, a comic book depicting Dahmer’s crimes”. Despite mentioning this in the documentary, the Netflix docuseries was ironically another “unwelcome reminder”. The families have a right to have their say. They have a right to fight; just as their loved ones did, all those years ago.