Remembering Queenie

Wakka Wakka woman Queenie Hart was only 28 when she died at the hands of a 'sadistic killer' in 1975. Now, her family wants to bring her back home.

Gudamulli!

There is a reason this newsletter is called ‘Presence’. It is built upon what Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has described as a notion of presence or act of presencing in her book ‘Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back’. Simpson does not outline a clear methodology on presencing or presence, but she describes what it means for her own nation through the experience of visiting an art exhibition: “It reminded us that we as Nishnaabeg people are living in political and cultural exile. Yet, it disrupted the narrative of normalised dispossession and intervened as Nishnaabeg presence – not as victim, but as a strong non-authoritarian Nishnaabekwe power.”

Over the past three years, I’ve been thinking deeply about how the media re-compounds the violence inflicted upon Aboriginal women through silencing, erasure, and representation. I consider ‘presencing’ a way that black media can contest these damaging representations through acts of ‘presencing’. For me, presencing is about making visible the overlapping forms of violence that impact Aboriginal women in life and death. If we see this, we can also see the everyday acts of resistances employed by Aboriginal women and their families against this violence. If we cannot see this violence, the violence is seen as being self-inflicted; a problem of our communities, and not a tool of colonialism. Violence was used to secure the interests of the colonisers, and it is through obscuring this violence that we in turn are seen as violent.

I hope to continue writing about these stories employing a methodology of ‘presencing’ in ways that pay tribute to the lives of Aboriginal women who have lost their lives to this colonial violence. This story on Queenie Hart, published in The Guardian today, is the first in what I hope will be many more.

If you would like to support Queenie’s family in bringing her home, please donate to the family fund via PayPal: @debbielwest - your contribution, big or small, will go a long way to helping heal an enduring injustice.

ON A rainy day in the Central Queensland town of Rockhampton, my father and I went looking for an unmarked grave.

We found the details in the burial index, and walked to the row, trying to find a grave marker. We knew there wouldn’t be a headstone. Carefully, Dad tried to make out numbers that were faded or had not been there at all, while I cross-referenced the headstones of each grave with the index, trying to match each plot to a number.

The people that were buried here in this section had all died in the mid to late 70s, and so we knew this is where we would find her. Dad asked her to tell us where she was. We walked slowly up and down until finally we found plot numbers 46, 47, 48, 49, and 50, and then 51. This was her resting place. But there was nothing to suggest she was buried here. The grass was freshly mowed and there were no flowers, no memorabilia saying who she was: aunty, cousin, sister, friend. There was nothing there to say she had died, or even, that she had ever lived.

We went to the shops and came back, bringing artificial purple flowers for her, and we placed them there in a tin vase garlanded with lavender. We stood silently in tribute to her, on Darumbal country, so far away from her home, as the rain fell on our heads. My dad stared at that spot of earth and said “I feel like this is the second time I’m meeting her”.

Her name was Queenie Hart.

Wakka Wakka woman Queenie Hart. (Supplied: Estelle Sandow)

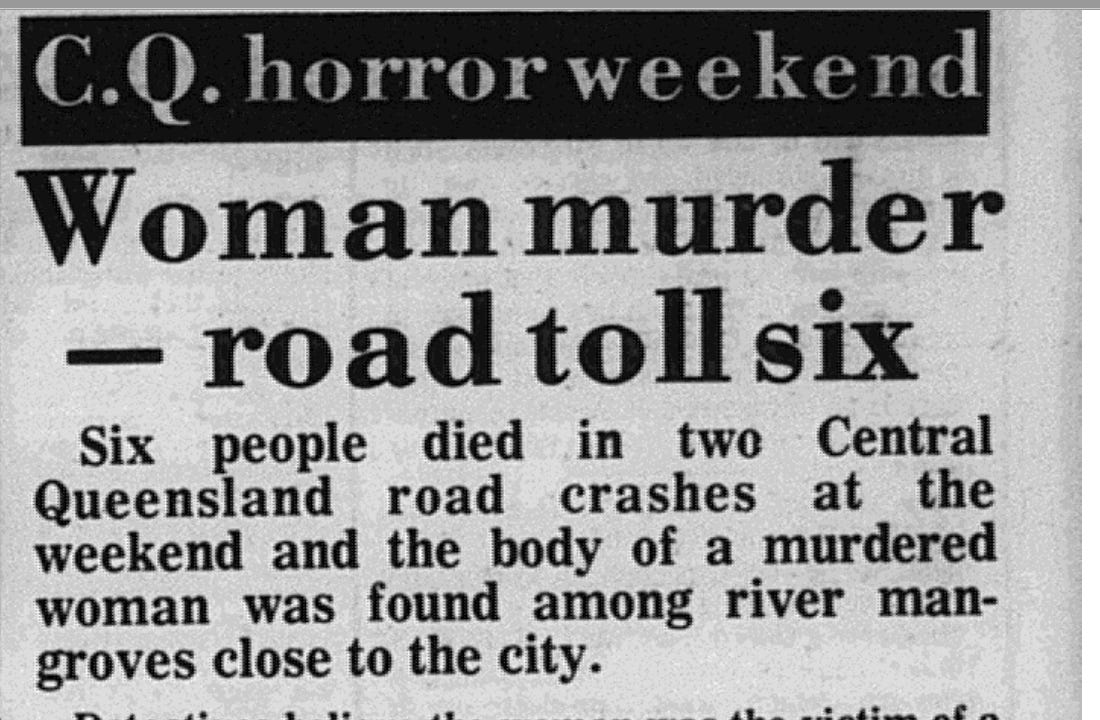

Queenie Hart had died in April 1975, on the banks of Tunuba – or the Fitzroy River – the large waterway that runs through Rockhampton. The local newspaper, The Morning Bulletin, had reported that “the body of a murdered woman was found among river mangroves close to the city”, on the front page, in a story that combined news of her death with the weekend road death toll. They had reprinted the graphic details of her injuries, stating that the police believed she had been the victim of a “sadistic killer”. She was only 28 years old.

A few months later, that same “sadistic killer” – a white man who was the last person to see Queenie alive – would have all charges of murder dropped against him, despite evidence pointing to his culpability. The case would not even go to trial. By the time the man had fronted court, he was no longer a “sadist”. He was a ‘fettler’. The courts and newspaper labelled Queenie a “prostitute”, despite there being no evidence to suggest she was working as a sex worker. While the man was described by his work, Queenie was dehumanised by it.

(The Morning Bulletin)

The coverage of her case was based around the descriptions of her wounds, and she had been wounded and violated, but she was held responsible for her own death not only because of her alleged occupation but also because she was Aboriginal. The newspaper called her “coloured” or “dark”. There was no mention that she was Wakka Wakka, that she was well-loved and that she was sorely missed. In Cherbourg, her home community, her mother Janey Hart was given few details, and when she tried to get her daughter home to be buried, she was denied by the superintendent in Cherbourg. Janey would never see her daughter returned to her. For 40 years, Queenie has been in that unmarked grave in Rockhampton, so far from home.

QUEENIE HART, like many residents of Cherbourg, wanted to be free. She had been born under the weight of the oppressive Aboriginal Protection Act, where the lives of residents were so tightly controlled that the bureaucratic language referred to them as ‘inmates’. She had found traces of this freedom within her families and friends, in the songs they sang at night under the trees, and in the love of her mother, who birthed eight other children but took in far more as her own. And when she was old enough to leave, she found her freedom in travel. Queenie Hart was a traveller, and she would come and go with the changing of the wind, but always return.

Queenie was quiet, and never ‘cheeky’, her childhood friend Melita Orcher remembers. Her mother had instilled in her a love of fashion, and she was always well dressed. She would take the tracings of tar off the stove and make the beauty spot by her mouth more prominent; she would use it to blacken her eyebrows. Her cousin Lewis Orcher, who had grown up in the family and was more like a younger brother (they were only one year apart), said that despite the deprivation on the mission, they had each other and this was their strength.

“She was a modest person,” Mr Orcher said.

“She was honest, she didn’t show off or anything like that. She had the little education you would expect from the Cherbourg school. She was a happy go lucky person. She was fun to be around. And at night time we would all sit around the campfires and we would all tell stories. She was just my sister. She was fun to be around and we were all happy to be around her. You couldn’t say she had a bad bone in her body.”

But Queenie would not stay on the mission. As a teenager, she was a member of the Murgon Impara’s Marching Team, which took her down to Melbourne and around Queensland. She was part of the team that won the Australian championships in 1960.

“We were very proud of that…. To see them girls win in Milton that day! When they said ‘Murgon Imparas they are the Australian champions’, everyone all screamed. It was really awesome. We all had tears in our eyes and Queenie was in that team,” Ms Orcher says.

The marching team presented a chance to go and see the world, and when Queenie left the mission, she pursued her love of travelling. She would hitchhike down to Sydney, and then to Toowoomba with Melita. When the Orchers moved to the Brisbane suburb of Woolloongabba, Queenie would turn up unannounced with lollies for the children. Melita remembers she’d go to the shops and come back to hear her kids tell her Queenie had come and gone. She loved children, but Queenie would never get the chance to have her own.

“We all got that itchy foot,” Ms Orcher said. “We couldn’t stay in that one spot. She could be here today and next thing she’d be gone the next morning.’

Melita remembers learning about Queenie’s death through the newspaper and having her sister Estelle Sandow coming into her, crying, to tell her Queenie had passed.

Down in Brisbane, Melita had welcomed a detective into her home, who had wanted her help to identify the body. She had told him of her memories of Queenie.

“(When the detective) asked me what I remembered, I said she had a beautiful tattoo on the left side of the ankle.”

She remembers that because she had asked Queenie about it, and Queenie had smiled because they weren’t allowed tattoos in Cherbourg.

“It was a nice little chain with bells on her ankle,” she said. “I always remember that. The police said we can’t identify this lady. I told them about the tattoo - she had a beautiful tattoo and I had told Queenie ‘I like that’ and she had said ‘I’ll take you to the place next time I get that money’.’

When she showed the police the photo she had of Queenie, and told him of the tattoo, they said that this was the woman who had died in the river.”

The descriptions of Queenie as a prostitute were also painful to her family, and those who knew her.

“The way they described her, as a prostitute,” could not be further from the truth,” Lewis says. “It was very damaging and completely out of left field… She’s not going to sell her body for a beer, that’s not the Queenie that I knew.”

“They didn’t really know her like we did aye,” Melita said.

“And I know her. I know what she’s like… she wouldn’t want to disappoint her mother,” Lewis said. “I felt what they were doing to Queenie was victim blaming.“That is one of the thing that really hurts, even now when I think about it, it’s really a gross injustice. The final indignity of someone who has been grossly murdered. It’s like well you deserve it, you’re a prostitute.”

Sex workers have a right to be protected under the law, just as any other occupation. But Queenie was not a sex worker, and her family wanted her remembered for who she was. And they had wanted justice for her but had been cruelly denied that by a legal system that viewed Aboriginal women as disposable and their deaths ungreviable.

WHEN I first heard about Queenie, I thought about what justice would look like in a case of a strong Aboriginal woman who had been the victim of violence not only in death but after it, through the courts and then the media portrayals of her. The white man has died and there is no prospect of ‘justice’ through the white man’s legal system. But there was a reason this case was speaking to me, and I saw it in the signs that kept drawing me to it.

These signs came first in the memories of those who lived by the river in which she died. My father is one of those people. Rockhampton may not have remembered Queenie, but the Aboriginal community did, and just like in Cherbourg they felt her absence even in the short time she was there. Dad had told me of how, at the age of 19, in 1975, he had stopped at a stop sign near the place where Queenie had died and had felt an eerie presence in the back of his car. He had always remembered that feeling and felt there was some sort of presence there, that it was her. That was the first time he felt he had met her.

A few months later, out of the blue, I received a message from a non-Indigenous man on Facebook. He wanted to talk to me about Queenie. At that point, I hadn’t told anyone about my interest in the story. We met in a local sporting club, and he told me why the case had stuck with him. He had been the taxi driver who had dropped Queenie and the white man off at the river that night. He had been interviewed by police, and he had been there at the courthouse to give evidence on the day that the charges had been dropped. He couldn’t believe what had happened, he had told me. I asked him why he thought there had never been justice for Queenie. He said, without a pause, “I always assumed it was because she was black”. I said, “I think you’re right”.

I had grown up in the place where Queenie had died, and I would find out there was another connection. I had met a friend of the family, Melita’s sister Estelle Sandow who had told me that when Queenie was in Brisbane, she would go to Woolloongabba to see Melita and Lewis. I work at Woolloongabba, in a house converted into offices, and every day I would think and speak about Queenie. Estelle would tell me this was the very same house that Queenie would come to, all those years ago. Melita says she would show up and peer through the window, the same window I look through as I make my morning coffee. When I expressed my shock at this ‘coincidence’, Aunty Estelle had just said:

“It’s that instinct aye”.

To Aboriginal people, these signs, these ‘instincts’, are not coincidences. They are the way our ancestors speak to us. If we listen, we begin to understand what justice looks like, what black justice means. For Queenie’s family, Black justice means bringing her home to country, to be with her family, and her ancestors.

DEBBIE WEST is Queenie Hart’s niece and grew up with Queenie’s mum – her grandmother – in Cherbourg. She was only 10 when Queenie died, and she had never met her Aunty. In fact, she had never known a lot about her Aunty’s death, because it had been too hard for her grandmother to speak about it.

“Nan never spoke about her death at all,” Debbie told me. “She never mentioned anything… I’ve never seen her in real sorrow. It was kind of a silent sorrow.”

“She didn’t really know the process of anything…’

Not only had the enduring injustice silenced her grandmother, but there had been another injustice: the cruel decision by the superintendent and bureaucrats in Cherbourg, who had refused the family the right to bring Queenie home to be buried. Debbie told me that her nan had always wanted Queenie to come back, and it had been one of her wishes before she died in the 80s.

At the time, Cherbourg had still been under the Act, and the resident’s movements and lives were still tightly controlled. Not only that, their money was strictly controlled, in a system that would later be known as ‘stolen wages’, where their pay and pensions were stolen and used to fund state infrastructure and amenities. Lewis Orcher knew this intimately: he had been forced off the mission and given an exemption because he had refused to work for free, and when he would try and return home to see Janey Hart, he would be escorted back off the mission by police.

But when Queenie died, Lewis had known that it was important for Janey to get Queenie back home to be buried. Janey had wanted to use her pension to fund Queenie’s return. Before Queenie’s burial, Lewis had gone to the bureaucrats in Cherbourg and had asked for permission to access the fund. But they refused. He had a good job in Brisbane and had offered to pay, but they had still denied the request to have Queenie returned to Cherbourg for burial.

“I kept saying ‘(Janey) is a ward of the state. She’s not going anywhere, you know trying to work something out. She doesn’t have any financial security or collateral to help bury her. But (the man) looked me in the eye. I could see I had him (on logic), but he was not going to concede at any point, and it made me very very mad.

“… so we had to do the next best thing and that was to go to the funeral in Rockhampton.”“… And very few people were able to go to the funeral.”

“In contrast (if it had been in) Cherbourg, three quarters of the settlement would have turned out to the funeral. Especially when its violence against a woman.”

It meant that not only had this injustice silenced her family, but it also meant they were robbed of their chance to remember Queenie, to tell stories of her, to tell the grandchildren of her, to continue expressing their love for her. There was so much that was stolen from them.

“I think that’s where (Queenie’s mum) really fell in silence and never spoke about it,” Ms West says. “She couldn’t afford to bring her own child back home to Cherbourg. She’s the only one buried away from home.”

IN THE CHERBOURG cemetery, there is a plot set aside for the Harts. Every one of Queenie’s eight siblings is buried there, as well as her mum Janey and dad Duker. Her family has already kept a spot for her, for when it happens. She will be buried with one of her cousins. In life, Queenie was never alone. But for 40 years, she has been amongst strangers, in that unmarked grave in Rockhampton.

The violence that killed Queenie, reborn in the callous apathy of the justice system, is the same colonial violence that denied her family the right to bring her home. But now her family will do it themselves, because this is justice: the ways we remember, the ways we bring our people home. Debbie did not know her aunty, but now she finds traces of her in what was left, knowing that they will have a place to go, on her own country, to grieve and mourn and remember her.

“When I think of my Aunty, I think of a butterfly. When I see a butterfly, they are skipping from one flower to another, going this way and that. And some of them are so pretty. She was always moving around, bringing happiness to everyone. A big piece of our heart lives in heaven, and soon we will know that is where she is.“We will know where she is.”

If you would like to support Queenie’s family in bringing her home, please donate to the family fund via PayPal: @debbielwest - your contribution, big or small, will go a long way to helping heal an enduring injustice. We will bring Queenie home.

I wish the following quote from your twitter had been included in the excellent and moving Guardian article.

"With Queenie's family's permission, @MartinGHodgson

began looking into ways to get Queenie home, and we finally have all the arrangements in place to bring her back home to Cherbourg, to be buried with her family - her mum and dad and her eight siblings and extended family."

Thank you Ms McQuire. Can you please confirm the paypal handle? I've tried a few variations but I cannot seem to get it to work.