The cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal people need to be heard

In 1988, Aboriginal teenager Mark Haines was found on the train tracks in Tamworth, northern NSW. Immediately, the police thought it was a…

In 1988, Aboriginal teenager Mark Haines was found on the train tracks in Tamworth, northern NSW. Immediately, the police thought it was a suicide. That was despite the family knowing that it was “out of character”, and despite the testimony of the train driver who found him, a railway investigator who saw that there was little blood, and a towel folded neatly under his head. The family went and did their own investigation, handing over evidence to the police themselves, because they felt they had weren’t taking the case seriously. They investigated a nearby abandoned car, opening the boot, and took what they believed was blood to the authorities. The police didn’t bother to fingerprint it, or didn’t see any connection with the crime. They even went as far to suggest that Mark may have stolen the car.

The thing was, Mark couldn’t drive a manual car.

The family knew how ridiculous this was. They knew the reason the police weren’t listening. And for thirty years, they tried to get anyone — the media, the police, and the public — to care. It wasn’t until Allan Clarke, a Gomeroi journalist who has a long history in Aboriginal journalism, came along. Allan has been investigating Mark’s case for nearly five years. He has produced stories for SBS’ Living Black, BuzzFeed News, NITV, and now the ABC, who tonight presented the Mark Haines story on Australian Story, and for the Unravel podcast.

The significance of Allan’s journalism can not be underestimated. While podcasts and television stories regularly sensationalise, feeding on a sickening appetite for true crime with no thought for the victims and their families , Allan carefully unravels the complexities of the case, situating it directly in the racism shown within Tamworth that deemed an Aboriginal teenager unworthy of investigation.

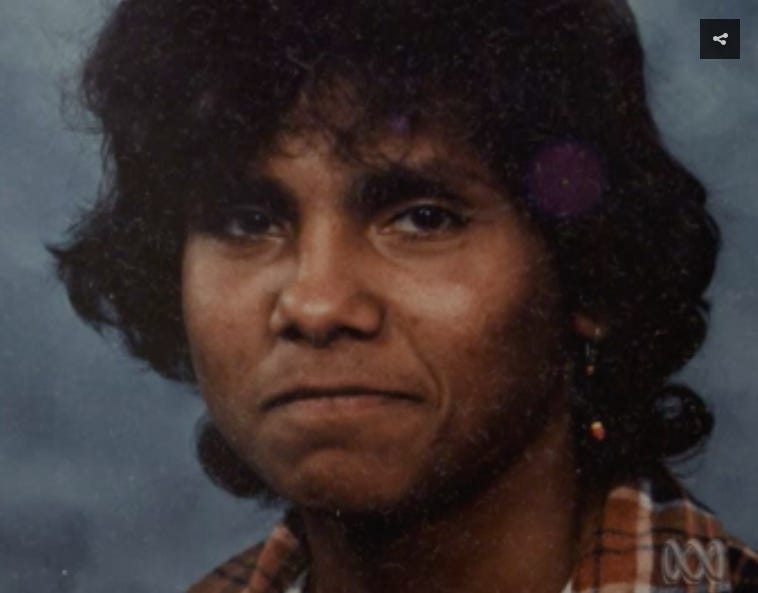

Allan’s interest in the case comes not only in the pursuit of justice, but also because he saw himself in Mark. Both grew up in a small NSW community, and both have large extended black families. They both come from the Gomeroi nation. Allan’s contribution is not only in upsetting the narrative of black victimhood and white sensationalism, but in stressing the humanity of Mark, and of acknowledging the humanity of his family, who still feel the trauma of his death, and the injustice that surrounds it. Through their testimony, we learn first about who Mark was — a smiling teenager, always happy, great at sport, and who could navigate both the white and black worlds.

It is also important because for too long, the numerous cases of unsolved Aboriginal murders have been ignored. Mark died in 1988, as protests ramped up around Aboriginal deaths in custody, for which there was a royal commission. It was in this time period, where there were several cases of Aboriginal people who died, and who’s cases were not properly investigated by police. It is an all too common story. The Bowraville children — Colleen Walker, Evelyn Greenup and Clinton Speedy Duroux — died from 1990–1991, and the original police investigation completely bungled it, focusing their attention on the community themselves instead of the white man who is now in the sights of the law for their deaths. Aboriginal teenager Karen Williams disappeared in Coober Pedy in 1990 and her body has never been found. Closer to my home, an Aboriginal woman named Linda, died in 1991 in the Fitzroy River, Rockhampton. Because of the racism from investigating police, the man who has been serving 27 years for her murder, is very likely innocent, in fact we have shown he is through the Curtain Podcast.

Watching Allan’s phenomenal journalism tonight, I was reminded again of the similarities between the cases of Linda and Mark. Both died within years of each other. And in both cases, police did not properly investigate all the evidence — including, the abandonment of a car that could have provided crucial clues to the identity of the perpetrators. Like Tamworth, in which black and white are separated by a boundary line in the form of a train track — the place of Mark’s death — Linda was found on the banks of the Fitzroy River, a natural boundary line that in the colonial era kept Aboriginal people cordoned to one side after curfew.

Too often, when we report on these issues, we are greeted with the usual ‘colourblind’ comments. ‘This isn’t a race issue!,’ they exclaim, as if it is in anyway helping their case, as if it is doing nothing more than comforting their own sensibilities. I know from following Allan’s investigation of Mark Haines’ death over the years, and in my own work, that the response from the police and the public always has a racial element. What other Australian family would be required to go out and collect their own evidence, simply to get police to listen to them?

There needs to be justice for Mark Haines, justice for Linda, justice for Bowraville and justice for Karen Williams, and all other Aboriginal people — men, women and children, who have suffered the apathy of police, media and the public, and for their families, who continue to live with the trauma.