The futility of 'white justice'

What does black justice mean when the white justice system can only offer hope?

Last night, SBS aired a new documentary about the Bowraville Murders, directed by the renowned Gomeroi journalist Allan Clarke.

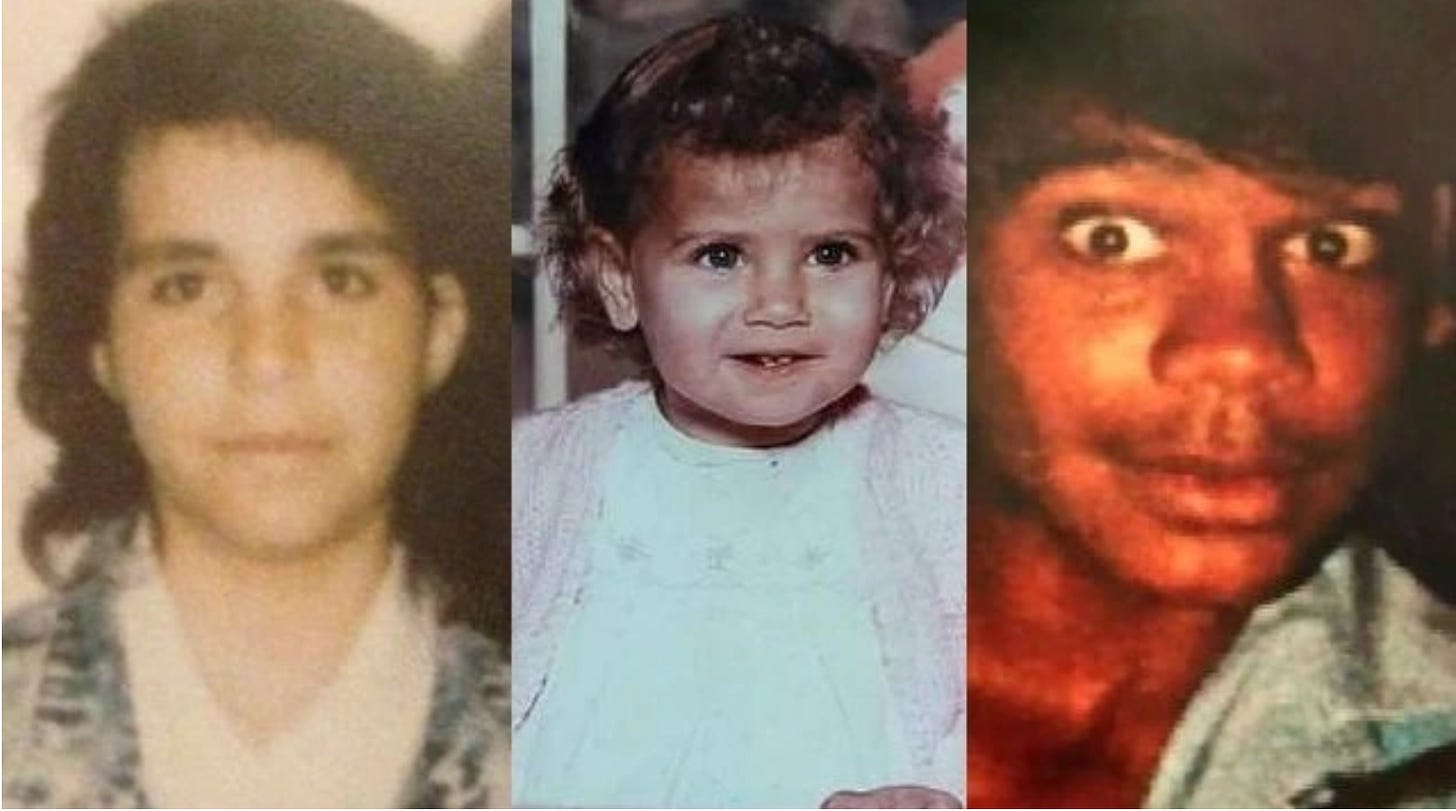

The film is the latest form of Black Witnessing; a piece of journalism that attempts to recentre the voices of the families of Colleen Walker, 16, Evelyn Greenup, 4, and Clinton Speedy Douroux, 16, who all died within months of each other, on the same stretch of street that runs through the Bowraville mission. The only person to be in the sights of the law was a white man who hung around the mission at the time of the murders, which occurred from 1990-1991. The man was acquitted of Clinton’s murder in 1993, and again in Evelyn’s case in 2006. He has never been charged over Colleen’s death, as her body has never been found and her family is still searching for her. The families have always been adamant that the best chances of a conviction would be if the three trials were run in one trial, similar to that which convicted the serial killer Ivan Milat.

There was one moment in the documentary that stood out to me. It was when Greens MLA David Shoebridge was speaking to the families in a closed room after another let-down, when the Court of Criminal Appeal had decided it was not going to send the man back to trial because of a legal debate over the word ‘adduced’ (see here for more information on this).

As Shoebridge informed the families of the situation, one man put his hand up and said:

“One word for three lives. How is that justice?”

This line cut through me.

The idea that justice for three Aboriginal children could come down to one word is outrageous when told through the lens of the Black Witness, but through the logic of the colonial courts, it is substantiated and seen to be legitimate. Through the voice of the Black Witness, we see the lunacy of this normalised logic that downgrades the worth of black children to a question of legal terminology even as their community rallies for 30 years to show that they were valued, and loved. One word for three lives. How is this justice?

The long fight that the Bowraville families have staged shows us the futility of white man’s justice, which the families are continually told they must pin their hopes on, even as it has shown time and time again that it will not deliver.

The film poignantly documents their long fight for justice spanning over 30 years, from the very first protests the families staged in 1991 when the police refused to investigate the deaths properly, to the numerous protests outside NSW State Parliament. It documents their win to enact historic law reforms to overturning the double jeopardy principle in order to get the man back before the courts, to the continual knockbacks from successive state Attorney Generals who refused to send the families’ application back to the Court of Criminal Appeal under these same law reforms. It charts the racism underpinning the original police investigation, which was first set up to investigate the community themselves, rather than the suspected serial killer, and which botched the investigation so severely that crucial forensic evidence was not properly taken (in fact was given back to the accused) and vital witness statements were not followed up.

A second investigation spearheaded by famous homicide detective Gary Jubelin following the acquittal in Clinton’s trial uncovered evidence that the NSW Police argued would be considered ‘fresh and compelling evidence’, but for which the legal debate emerged over whether it could be considered ‘fresh’ due to the clarification of the word ‘adduced’. To this day, the families have never received justice. They have never heard all three cases tried in the same court. Colleen’s case has never been heard at trial and her family are still searching for her.

I have been following the Bowraville case for over eight years, which is nothing compared to the long fight staged by the families. It is a story that has changed my life, my journalism, and my outlook; has made me entirely cynical of the prospect of ‘justice’ in the white man’s system. When the last knockback occurred in the High Court, I wondered what ‘justice’ could possibly mean in an Australia that was completely apathetic to such a huge injustice. At every turn, the families have been let down, and every single win has been due to relentless fighting in ways that the families of other murdered children would never be forced to undertake. And still, the white man’s courts refuse to accommodate them and continue to enact forms of violence that devastate the families and compound the trauma. The black trauma is highly visible, whereas the violence that caused it is not.

White Man’s justice could never be justice. It will always be ‘injustice’ because of the concessions it requires of blackfellas and the violence it inflicts upon them in this pursuit. It is a justice that requires more blood, more pain, more wounding. It is highly symbolic that the Bowraville families protested the Court’s knockback by staining the glass with red handprints.

In her essay on ‘Black Power’ in Meanjin, Chelsea Watego writes of her experiences in racial discrimination processes and how she chose to stand in her Black Power because of the continual concessions she had to pay to the process: “I realised that, even if I were to win, it would not be grounded in Black power, because so much had been ceded in an appeal to white sensibilities,” she wrote.

I came back to Chelsea’s words as I thought about all the concessions that the Bowraville families had to make to pursue justice in the White Man’s system. The system required them to concede some of their power, to become powerless, but they always stood strong in their Black Power. They have shown time and time again, they are not powerless; they have refused that imagining of them.

When the man was acquitted of Evelyn’s death, they did not go away as was expected of them (the DPP did not fight as it should have, and just ran the case, largely seeing it as unwinnable). They stood up at a community meeting and they said they were going to fight to overturn the double jeopardy laws.

When their application kept getting knocked back by the state Attorney Generals, when one AG Greg Smith told them they should just ‘get over it’ and ‘get counseling’, they did not go away, instead, they staged a protest outside those very gates. When the AG again refused to send that application back, they prepared to tell their story in full to a parliamentary inquiry, and their testimony, this testimony of the Black Witness, was so powerful that it forced the inquiry to tears. I was there as politicians from all sides of politics - the Libs, Labor, and the Greens - shed tears on the floor and paid tribute to the strength of their witnessing. On that day, the inquiry went above and beyond their terms of reference to call on the clarification of the legal term ‘adduced’ in order to get the application back to the courts. When they were given another blow, they stood strong, they stood back up, they began their next strategy. They never stopped strategizing. They never stopped planning. They always stood in their own power even in the face of a system that told them they had none.

There are so many indignities that the white justice system has forced upon the families that you can’t document them all in a half an hour. I’m thinking of the instances where phone calls aren’t followed up, the countless times the media have been informed of vital decisions before the families; of the time at Clinton’s trial when the riot squad police filled the court room; of the time in Evelyn’s trial where Black Witnesses were slandered as being drunk and when black parents were seen as uncaring and unloving of their children; of all the times the families were condescended to, where told they did not matter, had their voices ignored and overshadowed and silenced. These are the indignities wrought by the white man’s justice system; this is the continual violence of a settler colony in which the legal system is still an apparatus of oppression. The white man’s justice system could never deliver the form of Black Justice embodied by Aboriginal people and yet it is seen as the highest justice we should hope for.

In the documentary, I saw a form of Black Justice that did not require the continual blows that had been inflicted upon the families. I saw the power of the families, and this power was sustained by their love not only for Colleen, Clinton and Evelyn, but for each other. This black love is Black Justice, and it can’t be found in the white man’s courts, but in our communities - on Bowraville mission, in Sawtell, in Tenterfield, in Brisbane, in Sydney. The families stand in their love as an articulation of their power and this is a form of Black Justice. And we must stay here to witness it and to ensure that Colleen, Clinton and Evelyn are never, ever forgotten.

You touched right on how it is Amy. Thank you so much for this. I am in tears again after reading this. You told it exactly as it is. Love all these beautiful people who have showed the world how it’s done.

White justice will never give what our Aboriginal families offer 🖤💛❤️🖤💛❤️