Shattered Glass: The Death In Custody of Mark Mason Snr

Mark Mason Snr was shot by a cop in Collerenebri in 2010. His family never received a proper investigation, and 11 years later, his four children are still trying to pick up the pieces.

Gudamulli!

Today is a long read, but I honestly couldn’t make it shorter. This is a story that I’ve wanted to write for 11 years. It’s the story of Gomeroi man Mark Mason Snr, who was shot by a police officer in Collerenebri in November, 2011. Now the 11th anniversary of Mark’s death comes in the same week as two other tragedies - yesterday news broke that another Gomeroi man was shot by police in Sydney. And there was yet another death in custody at Shortland correctional unit. I was also supposed to publish this piece two weeks ago, but then news broke that the police officer who shot Aboriginal woman JC in Geraldton walked free from charges of murder.

This piece is a call to action for Mark and all other blackfellas who have died in custody. There was never any justice for Mark’s death, and there was very limited media coverage of it at the time. I feel like the family never received the support they needed, and which they deserved, so please, if you read this, share it far and wide. They will be holding a rally on the 10th anniversary of Mark’s death. It will be held on 11 November, at 11 am at state Parliament House in Sydney. This is a special request for media as well - media coverage is crucial in shining the lens back onto this enduring injustice. We need to build public pressure. This isn’t about gatekeeping stories - this is about working together to put pressure back where it should be. Please contact me if you need any more information - amygracemcquire@gmail.com

Shattered Glass: The death in custody of Mark Mason Snr

ON THE NIGHT that her dad died, Darlene Mason, who was only 18, walked into the Walgett Police station. It was 8:30 pm and her Aunty Marcia - Mark’s sister - had rung to tell her that her father Mark Mason Snr had been arrested.

Aunty Marcia didn’t have a lot of details, but she was already worried. She had told her niece to go down there and check on her dad, and specifically, to take photos of any injuries.

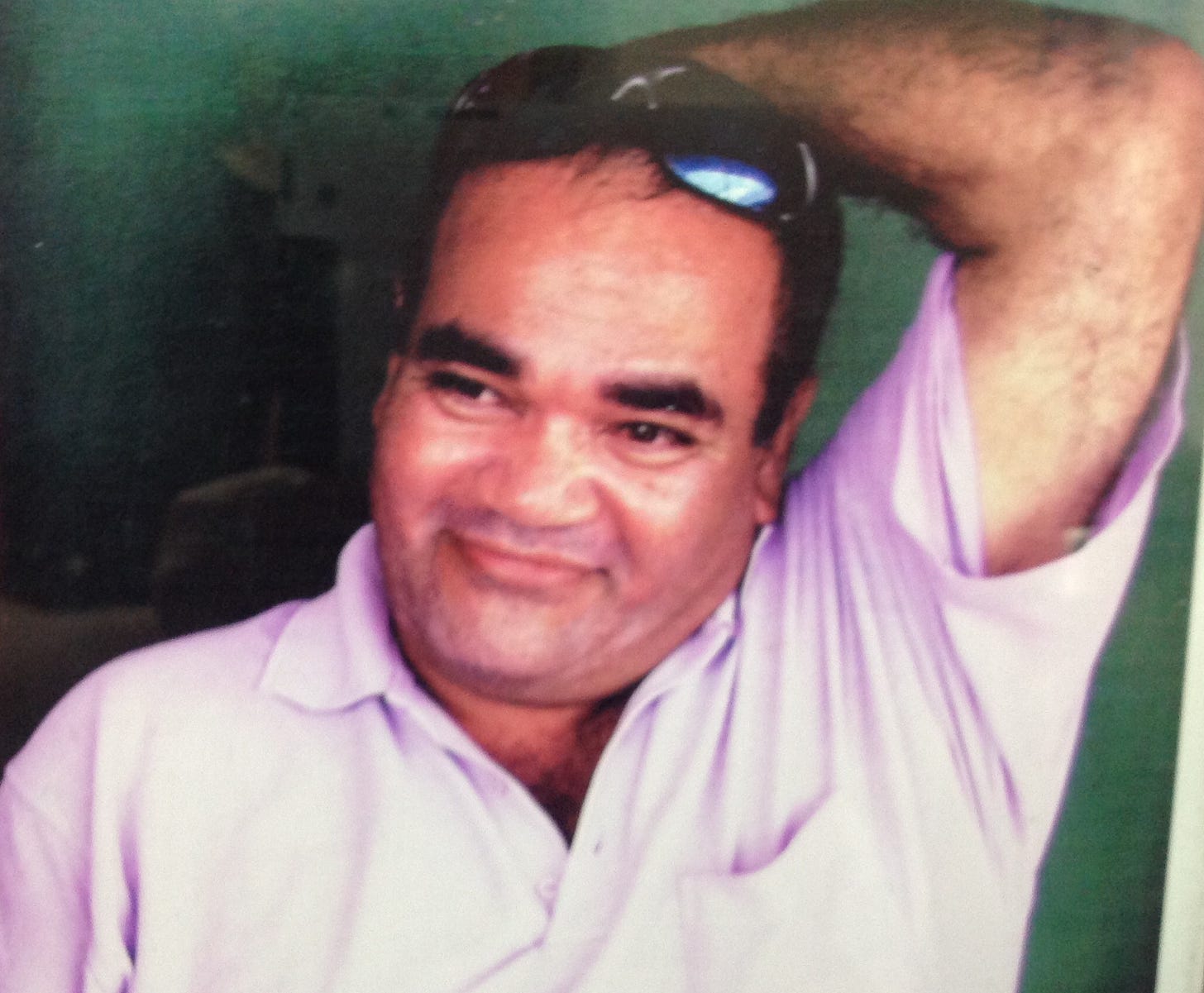

Mark had four children - Mark, who was named after him, Steven, Darlene, and his youngest, Trent, who was only 7 at the time.

As the only daughter, Darlene had been a ‘daddy’s girl’ so she says she “got away with a lot”. She had spent what would be his last birthday with him. He had had a win on the horses and had driven from Collerenebri to Walgett, to show her his new car.

“Every time he got a win on the horses, he would ring us up and ask us if we had any money. He would put some money into our accounts if we had none, or if he had a little win on the horses he would come home and ask us if we wanted anything, or if he wanted to shout us dinner,” Darlene remembers.

Mark Mason Snr was the type of father who was caring and attentive. He was a good footy player, and could have had a promising career down in the city, but had decided to move back home to Walgett, to raise his small family. Before he died, he was living in Collerenebri.

“He used to try and give us tips on the horses, and if we didn’t get it right, he’d go ‘ah you’re not like me’ ... but I’m not a gambler” his son Mark says, laughing.

Mark Snr liked having a bet, but it wasn’t the only knowledge he would impart on his kids. All his life, he had worked hard. He always had a job, at one time working at the local Aboriginal Legal Service as a field officer.

“He was a role model,” Mark Jnr says. “He didn’t drink or smoke. All the cousins that we did have around town, he’d tell them to come in for sleepovers, and he’d come in and play a game with us. He just loved having family around.”

But on the night that Mark Mason Snr died, the situation had reversed. Now, Darlene was going in to check on her father, the man who had always checked in on her. When she got the phone call from her aunty, she had made her way to the Walgett police station.

“(Aunty Marcia) told me when he arrives in Walgett, can you get some photos of him just in case he’s injured… because she told me what happened to him throughout the day,” Darlene says.

Darlene had immediately gone to the police station and had walked in, telling them that she was Mark’s next of kin.

“And so I went into the police station at 8:30 pm… and asked could they give me some information. And they told me no straight out. I asked, then, why can’t you give me any information? I’m his daughter, I’m his next of kin.”

But the police remained tight-lipped. All Darlene could do was wait, and that’s what she did. She sat outside the police station until 3:30 am. Every hour she ventured back inside, only to be told the same thing: there was no information about her father.

“Every hour to a half-hour, I would go into the police station. But the second time, I went in it was totally different from the first time,” she says.

“They were running around like they were getting their heads cut off. I didn’t think nothing of it because I didn’t want to think about what was happening with my dad. I knew my dad was supposed to be coming back in.”

Darlene kept ringing her aunty Marcia, calling at least seven times to hear what had happened to her father. It was at 3:30 am, after hours of waiting, hours of pleading for more information, that she heard her aunty crying down the phone.

“The last call she was crying. That was at 3:30 am. She was crying and I’m like ‘what’s going on aunty?’ She couldn’t speak to me for a minute or two, and then she stopped and pulled herself together. She said ‘we lost dad baby’.”

Even then Darlene didn't believe it. She didn’t want to move from her spot, where she was waiting for her father.

“I’m like no (we never lost him), he’s coming into Walgett. I’m waiting for him now. And I’m not going until they bring dad in here so I can get the photos of him.”

Darlene didn’t want to believe it until the next morning at 7 am, when the legal aid officer came and informed the family that their dad was shot by five police officers.

Darlene would later learn that her dad had passed at 9:30 pm that night, as she waited outside the police station, as she went into the station to enquire for the second time.

“That night, my dad didn’t arrive,” Darlene says, breaking down in tears.

Mark Mason jnr had been asleep overnight and had woken to a series of missed calls on his phone. He rang back, thinking ‘why are they ringing me so early in the morning?’

“It was my aunt calling me to tell me not to turn on the tv. She had devastating news… she said we just lost our father,” he says.

“I was only talking to him the night before, a day before he died. I was going out to Collie to see him and he was going to come back to Sydney for a while. My eldest daughter - they had a close bond and they used to ring each other every night. I just heard he got shot by the police, and then I saw on the stories on TV.”

For Mark Jnr, the situation was even more traumatic given the media’s reporting. Because he shared the same name with his father, the media put his photo on the news bulletins.

He always thought he should have taken them to court.

I FIRST heard about Mark Mason Snr’s death on the radio, while I was driving from Armidale to Tamworth. The short news report said a man had been shot by a police officer in Collerenebri. Before he had even been named and before his Aboriginality had even been mentioned, the police were already absolving themselves. I knew immediately, that this must be another black death in custody.

In the news coverage that followed, the police continued to undermine any form of independent investigation, even before one had been called. In the direct aftermath, Acting deputy commissioner of field operations Alan Clarke told the media that Mr Mason had led a “determined attack” on police, who had no option but to use lethal force.

“Police have dealt with a life-threatening situation,” Superintendent Clarke told the media.

“It would appear they have exhausted all their options, prior to resorting to lethal force, and on the information before me, I certainly believe that officer had no other option and resorted to the only remaining option they had to protect their own lives.”

But Mr Mason’s family were given no such platform to ask their questions. They had their own which were overshadowed by the police insistence that the force that killed a much-loved Gomeroi man had been ‘justified’.

“They were saying nothing happened, Mark did this, Mark was in the wrong,” Mark Jnr says about the police. “They were having meetings to calm the community. The police were everywhere. They were thinking if we showed up to the meeting there would be an uproar. They were calling all the police for support.”

Mr Mason’s family though had valid questions: How could Mr Mason, who had a heart condition, be seen as a threat when he had been cornered in a small house by five police officers? How could he be seen as a threat when he had been tasered twice and doused in capsicum spray? How could he be the threat when he had a tire iron, and they wielded their guns? Who was the one in fear for his life, when it was the black man who had lost his?

The police response prompted an angry reaction from the chair of the NSW Aboriginal Land Council Bev Manton, who was my boss at the time.

“There have been several premature media statements made by the police before the facts have been fully correlated and the investigation completed,” Ms Manton said.

“One of these claims has been the conclusion that the police had exhausted all other options. I find it difficult to believe the police would be forthcoming in making these sorts of statements if it hadn’t been one of their own involved.”

That same week, I received a call from Ms Manton about Mr Mason’s death. She had contact with the community, who were outraged and in mourning. She asked that I attend the funeral for Mr Mason, which was being held in Walgett, his home community, where he had spent most of his life.

The next week, my colleague Chris Munro and I flew up to Moree and made the drive to Walgett for the funeral. On the way there, we had stopped in Collerenebri, and driven around till we found the house where Mr Mason had died. It was small and contained and I thought of the fear that had driven him inside.

In Collerenebri, they have a unique process of remembering. The cemetery is a place of storytelling; a place of remembrance.

In the cemetery, they burn glass and use it to decorate the graves of their loved ones. It is a long process where the colours are carefully selected. They assemble the right bottles, wash and dry them, and then a hole is dug where the bottles are placed on hot ash. They wait for an hour, and then they collect the glass, breaking it into pieces, and then adorn the graves with it.

It is a powerful ritual of remembrance, as academic Heather Goodall describes it: “When regularly maintained and replenished, the glass forms an impenetrable cover, keeping weeds from growing on the grave and protecting it from disturbance by animals and weather. But it is not only for protection. On approaching the graves from any direction, the ‘crystalled’ glass catches the light, sparkling like water”.

This is the place Mark Mason Snr died and where he lived. It is a place where they ensure their loved ones are remembered even after they are gone; a place where the memories of who they were are never forgotten, but always catch the light.

When we arrived in Walgett, we had walked around the small town, and I was shocked, that despite Walgett being nearly 30 percent Indigenous, on this day, there were few blackfellas on the street.

Instead, the town was filled with riot squad cars. We went to the local takeaway where the cops filled in behind us in their blue uniforms, their guns to their sides, and joked and made light conversation, as they ordered their dinner. We would learn there had been an increased police presence in the town in anticipation of Mr Mason’s funeral.

The next day, at the funeral, people spilled out of the sides. There were so many people there, it felt like the whole town had come, and the sense of injustice hung in the air.

As Mark’s coffin was carried out, a woman had cried out: “They killed him!”. We all knew who “they” were, but despite their noted presence in the town, “they” had not turned up to the funeral.

Instead, I learned later, they had made regular patrols of the wake, and the houses of Mark’s relatives as they continued their mourning into the night.

Riot squad cars lining the streets of Walgett on the day of Mark Mason Snr’s funeral.

Not only that, in the lead-up to the funeral, the local bottle shop shut its doors. Mark Mason was related to TJ Hickey, the young Aboriginal boy who was chased to his death by cops in Redfern, sparking the Redfern riots.

“They said Mark Mason is TJ’s cousin so there’s definitely going to be a riot in Walgett,” Mark Jnr says.

Instead, the children had a close gathering in their mother’s house, remembering Mark, and strumming the guitar, while police cars rolled by.

To this day, Mark Jnr is still asked about whether his family were planning anything that night.

“They ask, sorry about your dad, did you plan anything that night? I say mate, I just fucking buried my father.”

Blackfellas can’t even mourn in peace without being suspected of a riot.

Mark Mason Snr’s family protesting for justice in Collerenebri in 2014.

IT WAS THREE YEARS after Mark’s death that a coronial inquiry was held in Dubbo. At the time, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, there was the longest backlog in death in custody cases in a decade in a half.

Just as Darlene had waited for hours on the night her dad died, the family waited and waited for what the coronial process is supposed to deliver - a form of truth-telling, and potentially, a call for accountability.

But the family would never get that; in fact, it would not even come close. I attended one day of the inquest in Dubbo. The police contingent had filled one side of the room, while Mark’s family had been there, on the other.

There was no one there to support them. In their presence, they sat there, alone, for Mark.

The inquest lasted only three days, and the coroner legitimated the police version of events, stating while Mark Snr’s last moments were “horrifying”, while "he would have been hurting a great deal”, ultimately the police use of force was justified.

The coroner delivered no recommendations, and the report is no longer on the Coronial NSW website. It was only six pages at most, and when I read it, I remembered it centering on police protocol on taser use. In its place is another report, from the coroner knocking back the family’s request for further information.

There has never been an independent investigation into Mark’s death. It was a situation that was savaged by Greens MLA David Shoebridge, at a protest for Mark in 2014: “The police investigate their own actions. We’ve seen this time and time again where you have police investigating police, and you don’t get a just outcome,” Mr Shoebridge said.

“You don’t get a fair day in court. You don’t get a fair representation of the evidence to the coroner, and you don’t get a fair outcome. We need to stop this legal structure that has police investigating police and we need a genuinely independent body to… hold them to account when they do the wrong thing.”

Mark’s family wants the right to question every part of the police version of events, from when Mark was first chased by police, to the circumstances that culminated in his death.

In addition, there are questions even prior to that day, like the glaring one: why was Mark Snr targeted in the first place?

Leading up to his death, Mark Snr had been subject to intense police surveillance. He had been on the Suspect Targeting Management Plan (STMP), which Sydney Criminal Lawyers describes as a “secretive blacklist that the NSW police force had been running since 2000”.

“Those placed on the list receive increased surveillance, which includes being stopped and searched, as well as having police visit their home,” the site says.

Aunty Marcia Mason-Hoskins told Sydney Criminal Lawyers that: “it meant that he had the police sitting across from his home three times a week for half-hour intervals. It meant that his car was searched. And he was searched. If he had passengers in the car, they too were searched.”

He had been on this list because the police believed he could commit crimes in the future. He had been suspected of illicit substances, but Mark never drank alcohol or smoked and he had never been found in possession of illegal drugs in all of those searches.

The intense surveillance had been taking its toll on him.

”One time he saw (the police) at the petrol station, and they said something like ‘here’s this black c***t is again,” Darlene says. “When he told us that, I said ‘dad you need to be careful. They’re really after you.”

Mark had already been targeted as a ‘threat’ to police, despite the fact there was no reason for him to be on that list. He was just a black man living in a regional town.

Then there is the footage of his death, taken from the end of the taser. Mark Jnr has seen the video and he can describe it in brutal detail. The footage has never been released, because it is traumatic, and at the time the family did not want it to be shown. I knew that a prominent television program had been interested in the story, but had only been willing to run it if they could air the last moments of Mark’s life.

But why should black families be forced to show the death of their loved ones in order for questions to be asked, in order for their stories to be aired, in order for their testimony to be believed?

To this day, Darlene has not watched the video. When it was shown in the coronial inquest, she had walked out the door.

“I wasn’t strong enough then (to watch it),” she says. But she could still hear it from her position outside.

“Ad I still hear it today. I can still hear him screaming,” she says.

ONE OF THE MOST tragic aspects of Mark’s story is the guilt his children still hold. On talking to them, they say they wished they had protested sooner. They wished they had spoken to the media. They think of what they could have done differently, to fight for justice for their father. In some ways, they feel they let him down.

But they never let their dad down. There is no ‘right’ way to protest; sometimes silence is a protest, in its own way because resistance is in caring for each other, and healing each other. There is no one strategy to fight a system that tells us there is only one form of ‘justice’, and it is be found in the same system that denies us ‘justice’; that sees our deaths at the hands of police as ‘legitimate’; that says black men are innately threatening.

From the very early days, as they still struggled to process their grief, as they still cried in the midst of an unknowing, as they were told by the police that it was their dad who was the threat, as they were told not to question the police version of events, as they saw the media fall in behind the blue line and not the black one, as they were asked or were suspected of staging a riot, they never forgot their father.

A decade on, they have begun the process of assembling the glass that had shattered on that night, on November 11, 2010. They are bringing together all of those pieces and placing them on a fire that has never dimmed, a fire that has been sustained by the overwhelming love that children have for their dads.

When this shattered glass is finally pieced together, it will be not only to remember, not only to find a form of justice that has been long denied, but to uncover a truth that will always, catch the light.

* On November 11, 2021, there will be a protest for Mark Mason Snr in Sydney. It will begin at 11 am at NSW Parliament House.

I watched SBS last night - Karla Grant's "Insight" - a panel of significant people - families of those murdered by police and gaolers - and those working to right the wrongs - Keenan Mundine (deadly Connections), Dylan Voller (survivor of spit-hooding/Don Dale), Jeffery Amatto, Deb Kilroy (Sisters Inside), Shane Phillips (Tribal Justice), George Newhouse - and others appearing including Leetona Dungay and Paul Silva. Grace and passion in their determination to both gain justice and to act to protect more young people from being killed by police and gaolers! And to think that Leetona Dungay has had to take the David Dungay murder to the UN in order to try and seek some justice! Astounding (or par for the course in the kind of police state suffered by First Nations people here in Australia - in NSW. Your tribute to Mark Mason and his family and the ugliness they have suffered now for so many years is equally moving. Thank-you.